[ad_1]

What happens in Vegas stays in Vegas. V. Ravichandar, 67, thinks this line about leaving behind the consequences of past indiscretions is key to tackling many of Bengaluru’s problems. “Koramangala’s garbage should stay in Koramangala. It cannot be dumped in a village, spoiling the groundwater there for the next 100 years.” It’s his way of saying that neighbourhoods and households should solve some problems locally. “The current way the city is working is dysfunctional,” he adds.

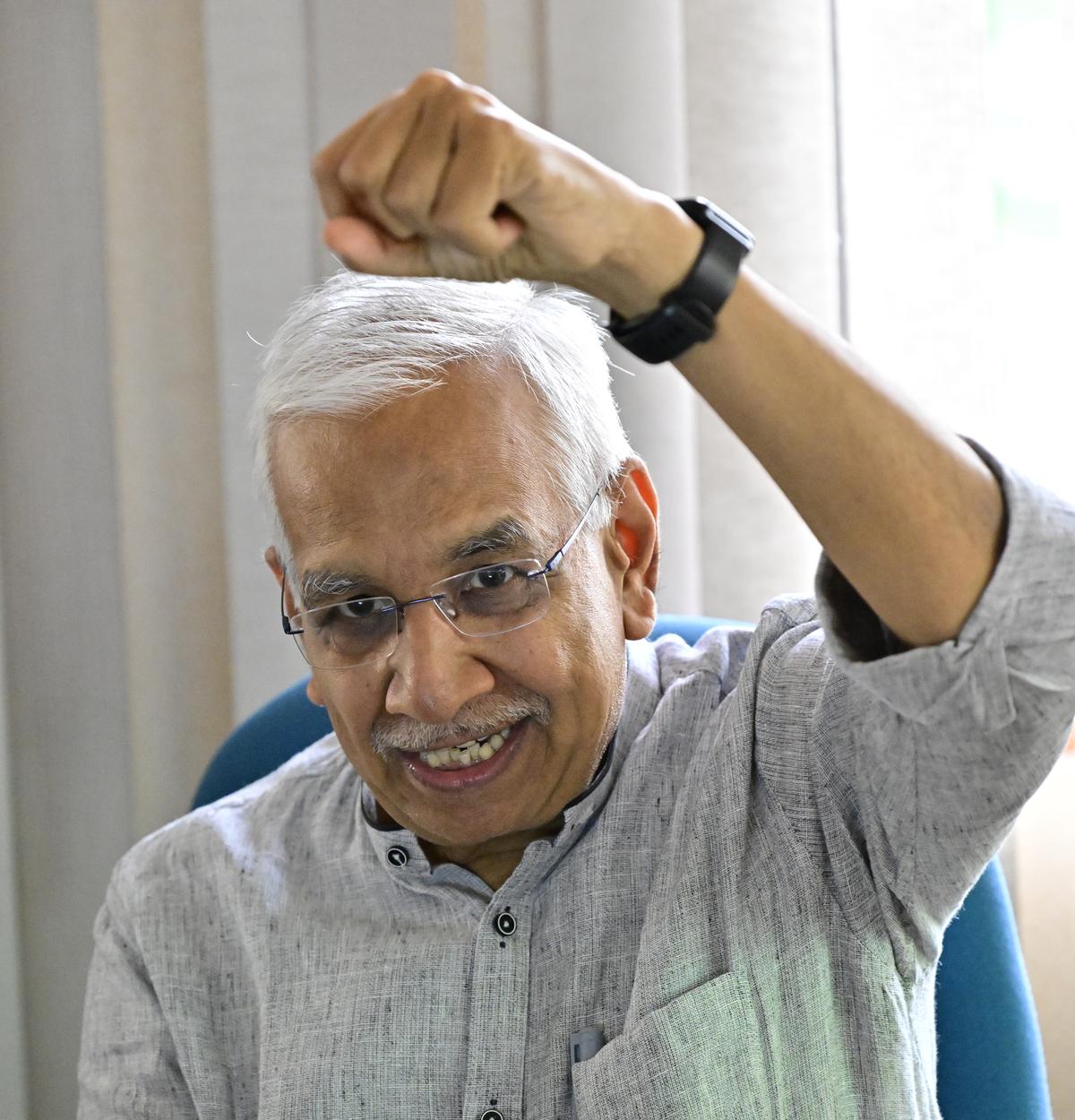

Ravichandar, or Ravi as everyone calls him, describes himself as a patron saint of lost causes and a town crier, with emphasis on crier. He’s actually quite cheery, that rare combination of talker and doer. If we could use AI to replicate his enthusiasm and drive, every Indian city could do with at least a dozen of him.

These days he has enlisted the help of the local government to ensure that you bond with your neighbourhood and the larger community. “As we are getting more and more polarised, we need spaces where conversations can be had,” he says. He has turned the spotlight on a problem that gets little attention and even less funding.

Celebrating the Garden City

Ravi says that in his 24-year struggle as a civic evangelist, he was involved in three big successes: the self-assessment scheme of property tax; pedestrian-friendly Tender Sure roads; and making Lal Bagh Botanical Garden (Bengaluru’s biggest park) sustainable forever. “I have hundreds of failures,” he says, including among them the recent Greater Bengaluru Governance Bill that he helped conceptualise and which the state government changed before tabling, making it “anti-citizen”.

He believes in distilling big issues into basic principles. “If you have a dream that one day we will swim in Bellandur Lake [Bengaluru’s infamous foaming water body], then work backwards when decisions come to you,” he says. “Ask yourself, ‘Will going down this route help me swim in the lake or not?’” The thinking is inspired by Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew who, in 1969, announced he wanted officials to clean up the polluted Singapore river and other water bodies so “fish, water lilies” and assorted plants could grow. They worked for a decade to achieve this dream.

Ravi has been on innumerable committees, including the influential Bangalore Agenda Task Force, and though he has the ability to keep going despite failure, the lack of control when working with the government was responsible for his pivot into the areas of arts and culture in 2010.

V. Ravichandar

| Photo Credit:

K. Murali Kumar

He’s raised money for 12 years for the Bangalore Literature Festival, likely the only big community-funded book festival in the country. Until the start of this year, he helmed the Bangalore International Centre, a group effort to resurrect shrinking public spaces. These days, he’s masterminding a series of cultural events in Bengaluru’s neighbourhood parks that will culminate in a year-end celebration of the city.

He wants to recreate the Edinburgh Fringe Festival in Bengaluru and visited Scotland this year to understand how one of the world’s biggest annual celebrations of art and culture unfolds. “They do 2,200 events a day across 600-plus venues over 25 days,” he says, adding that despite the scale, he saw no major visible corporate branding.

He began work on this project last year as chief facilitator of the venture Unboxing BLR. This year, the 16-day BLR Hubba festival is scheduled to begin on November 30. In a few years, it will likely be a go-to event if his past work is any indication.

‘Reviving public spaces gives me joy’

Ravi admits it’s difficult to replicate his work-life model. When his spouse Hema Ravichandar — who, for a while, was the only woman on Infosys’ founding management council — got stock options, the couple could focus entirely on pursuing their interests. Hema opted to continue working in the field of human resources and mentorship, while Ravi decided he would “just jump into causes”. “Chequebook charity is fine too, but my kick has been in getting engaged, getting involved,” he says.

Ravi is the first to admit that he can’t distinguish Hindustani music from Carnatic or that he doesn’t understand classical dance. But all his forays into the world of arts and culture have centred around one key aspect. “Our public spaces are shrinking. I want to resurrect them,” he says. “Creating community gatherings and reviving public spaces gives me great joy.”

He’s immersing himself deeper into the world of arts with a new venture called Sabha, an arts and crafts centre housed in a 170-year-old building. Though most of the work he’s done until now has been pro bono, this is his first family philanthropy venture. It promises to be a space that will draw all kinds of people.

Ravi hopes that some day people will talk less about Bengaluru’s traffic and garbage, and focus instead on something that unites us. If dreary Edinburgh can become a cultural hub, so can this city, he believes. “Cities can be celebrated and positioned in a manner that is positive and equitable,” he says. That’s the hope anyway.

The writer is a Bengaluru-based journalist and the co-founder of India Love Project on Instagram.

Published – October 03, 2024 01:44 pm IST

[ad_2]

Source link