[ad_1]

A leading Mumbai hotel once catered a corporate banquet with a dish from every Indian state. It was strictly vegetarian and for the Northeastern states the chef was clearly at a loss. He ended up offering six bamboo shoot dishes, and boiled rice for Tripura. No banquet has ever used so much bamboo shoot.

The edible shoots are undeniably important in the region of lush hills and river valleys casually marginalised as the ‘Northeast’. It is a place with complex histories and very diverse communities, crossroads for trade, war and displacements and a reservoir for remarkable biodiversity. A wide variety of plants and animals are foraged and hunted there, and fermented, smoked and processed in multiple ways. There is much more than bamboo shoots.

Cooking Nagaland’s fermented bamboo shoot and fish, Lotha-style

Foraging for tender bamboo shoot

Journalist Hoihnu Hauzel was one of the first to try to cover the Northeast’s food diversity. In an acknowledgement of past efforts, her memory of the project is the first essay in Food Journeys – Stories from the Heart, a deeply impressive anthology edited by Dolly Kikon and Joel Rodrigues. Hauzel was a cub reporter in Delhi covering food events that celebrated the traditions and ingredients of places around the world, which made her wonder about doing it for the Northeast.

She sent a proposal to a publisher and was immediately accepted, which was when the enormity of the task dawned on her: “Nagaland has over 16 tribes. Manipur has over 29 tribes. How would I include all of them?” The Essential Northeast Cookbook, which she produced, was revelatory for its time, but also hinted at how much more there was, and how difficult it would be to do it all justice.

Galho (rice with vegetables)

Books which followed, such as Purabi Shridhar and Sangitha Singh’s The Seven Sisters: Kitchen Tales from the Northeast, and Aiyushman Dutta’s Food Trail: Discovering Food Culture of Northeast India, helped illuminate the subject, while struggling with covering such diversity from inevitably limited perspectives. Which is where Kikon and Rodrigues’ anthology scores. They embrace and give voices to the diversity, allowing us to hear directly from the different peoples of the region.

Farmers carrying home foraged food

Patchwork of memories and experiences

Kikon and Rodrigues are anthropologists, as are several writers in the collection. Others include academics, a singer, a dancer, a novelist, photographers and documentary filmmakers. Their subjects include a Muslim widow who makes puffed rice, tea plantation workers, market vendors, a chef trying to keep her food traditions alive in Delhi (she notes, ironically, how it was easier to find ingredients like offal while working in the UK), and many older women relatives of writers, whose food lives on in their memories.

Cooking chicken curry over a fire

This patchwork project works so well it should be considered for other attempts to capture the diversity of food systems in different parts of India. Any lack of cohesiveness is more than made up by the sense that this is how we actually cook today, with all the realities of unreliable food supplies, packaged products, struggles for identity expressed through food, and the influences of the Internet.

Cookbooks often try to capture idealised versions of cuisine, passed on from grandmothers and untouched by current concerns, but Food Journeys acknowledges that real life is different. Academic Juliana Phaomei recalls her grandmother through the fermented mustard leaves she used to make, but when she tries to recreate it, her mother tells Phaomei that she’s learned part of the method from Chinese YouTubers. Performing artist Babina Chabungbam notes the importance of the Machal’s spice mix brand for Manipuri food, both in and, increasingly, outside the state.

Kneading mustard leaves

The traditional ganaeng tamduikou (container for mustard leaves chutney)

Some themes recur. Food used to discriminate against people from the Northeast is well documented in articles and the film Axone (2019), but it happens in the region too. Techi Nimi, research scholar in anthropology from Arunachal Pradesh, recalls boarding school questions about whether people from Arunachal ate cockroaches, elephants and dogs. But another kind of prejudice raised its head in a highly Sanskritised school where students were only allowed to eat with their hands, even Maggi noodles. When she smuggled in a spoon it was confiscated: “Our dining-in-charge looked me dead in the eye and said, ‘Oh, finally you tribals have learnt how to eat with spoons.’”

Arunachalee food consisting of rice, meat and bamboo shoot, served on a local leaf called okam foraged from the jungle during special occasions and festivities

Raising uncomfortable questions

A larger theme is whether the foods documented will survive. Tourism plays a complex role. Professor R.K. Debbarma’s homestay host in Khonoma, a village in Nagaland, tells him visitors from Guwahati come with lists of what they won’t eat. Debbarma writes that he avoids three types of Northeastern restaurants: those “with bold claims to being for families, or authentic, or pure vegetarian”. Independent writer Rini Barman’s study of the Haflong market in Assam notes how Indo-Chinese food is becoming more popular at food stalls. But she quotes Kanak Hagjer, a local food blogger, who says tourists are picking up a taste for traditional foods: “It will bring more exposure to ethnic cuisines.”

A rice meal at Mao Gate, Manipur, comprising boiled vegetables, uhti (peas cooked with soda), pork curry, and laphu (banana stem) eromba

The influences aren’t just from the rest of India. Lalchhanhimi Bungsut, a student of anthropology, notes how shops in Aizawl, which never stocked Mizo foods, now have Korean foods, presumably an offshoot of the Northeast’s K-pop boom. “The world is now accessible at home — but is there a way to build it a room without kicking out our traditional food?” However, this region, located where India, China and Southeast Asia meet, has always been willing to take on new foods, as lyricist and singer Ronid Chingangbam recalls with his grandmother’s recipe for tinned fish, sourced over the border from Myanmar and cooked with local herbs.

Entrepreneurs in Manipur are experimenting with new spice mixes that cater to shifting local tastes

Neivikhotso Chaya’s essay on rice beer captures many of the ambiguities around the past and future of foods of the Northeast. In a Naga restaurant in Bengaluru he’s surprised to find rice beer for sale. “Back in Nagaland it would only be available in poor neighbourhoods, from families struggling to make a living.” His family was one of them and he recalls the eternal presence in their homes of the rough rice used for brewing, which they also ate when money for other foods was scarce. They would unmould a large pot of rice and pretend it was a cake.

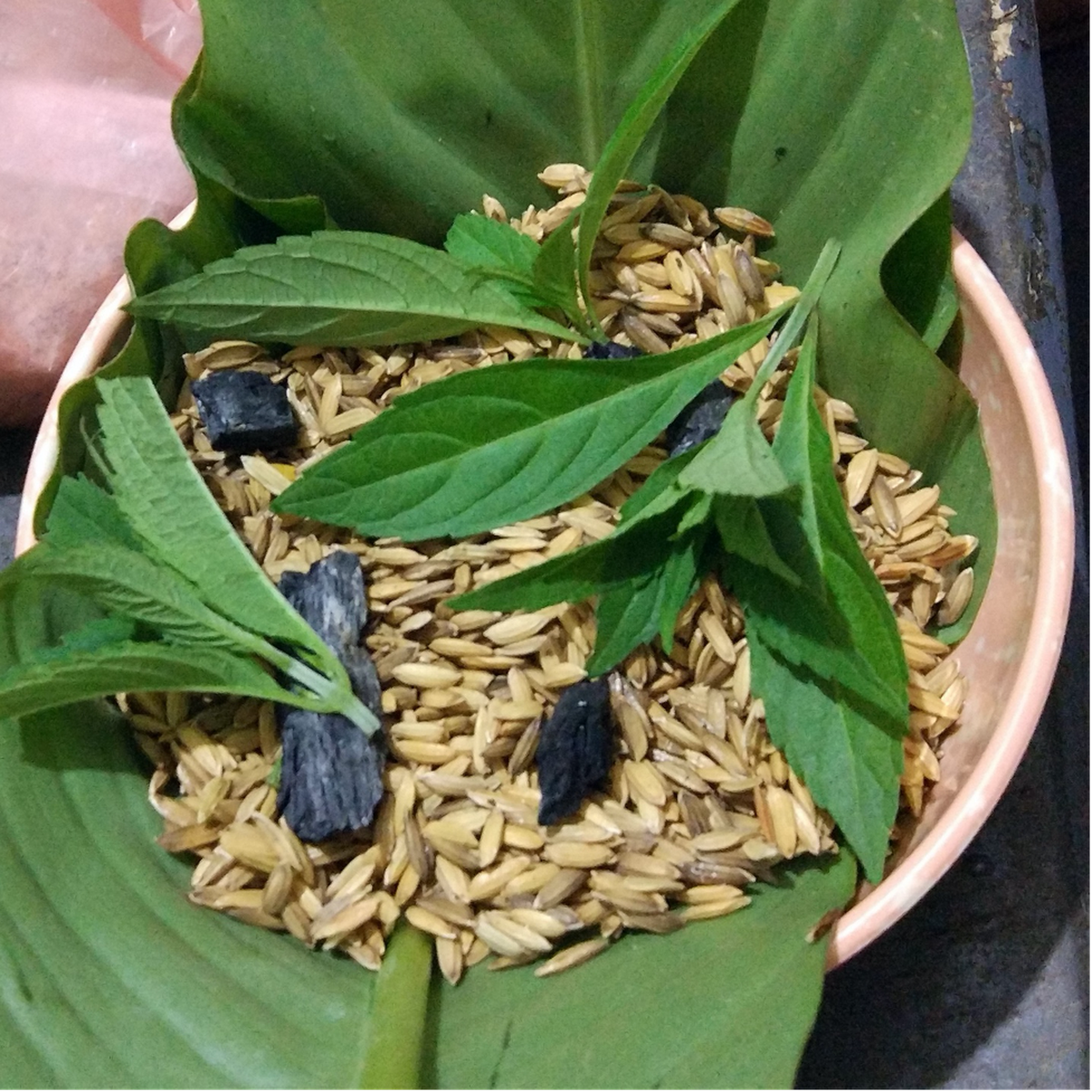

Sun-drying the rice with charcoal

A woman preparing rice to brew alcohol

Distillation, during the brewing process

But Chaya was also acutely aware of the shame attached to rice beer sale. Neighbours made rude remarks about them and people coming to buy would enter from the back door so as not to be seen. He came to resent his mother for making a living this way, and eventually she found a way to hire a room where the children could stay away and study. Today rice beer is on sale at the Hornbill Festival and those selling it are seen as promoting Naga culture. But has this really changed the status of poor people, like Chaya’s mother, who make it to survive?

Food writing in India often avoids uncomfortable questions like this, and it is to the credit of Kikon and Rodrigues, and Zubaan Books as publishers, that they allow the writers in Food Journeys to raise them.

[ad_2]