[ad_1]

Hot and humid climates can be one of the hardest climates to adjust to, with relentless perspiration and discomfort, and we often feel relief only on entering an air-conditioned space. For people used to modern-day apartments and offices, it is almost impossible to imagine being comfortable in these spaces without ACs. Yet, when we think of traditional homes in Kerala or Tamil Nadu, do we associate them with this same sense of unease?

Laurie Baker at work.

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Laurie Baker, one of India’s prominent proponent of climate responsive architecture, writes about the time he first discovered vernacular traditions, “…wherever I went, I saw in the local indigenous style of architecture, the result of thousands of years of research on how to use only immediately available, local materials to make structurally stable buildings that could cope with climatic condition… an incredible achievement that no modern, 20th century architect I know of has ever made.” Baker built hundreds of houses across Kerala inspired by these techniques, rejecting what had become the accepted modern practice.

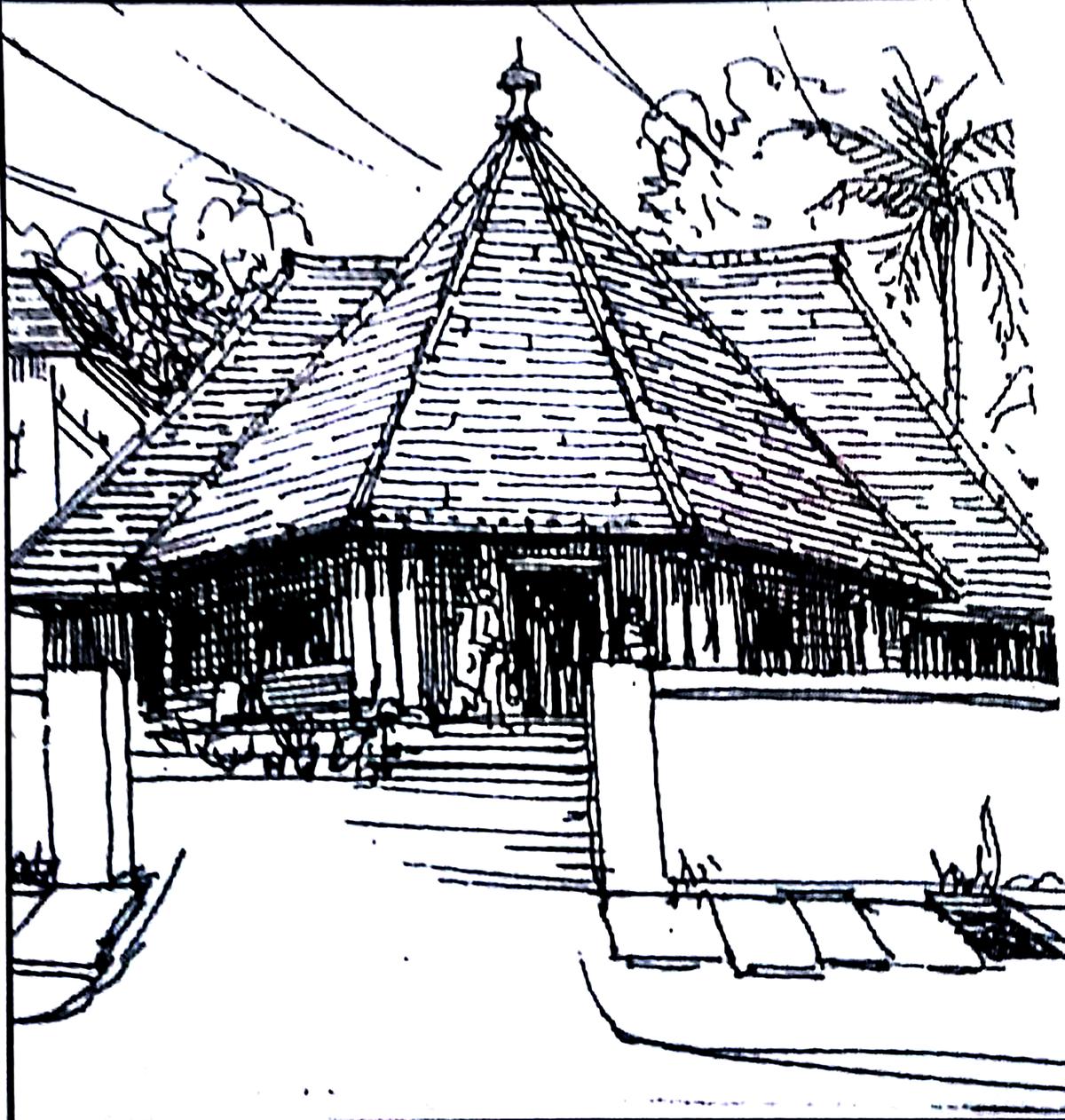

A sketch by Laurie Baker.

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

The interiors of a house built by Laurie Baker in Thiruvananthapuram.

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

The roofs have overhanging eaves, which shield the wall from direct sunlight and rain.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images/istock

Kerala has hot, humid, and wet climate. So structures were built with steeply sloping with country tiles, that allows water to drain off and keeps the indoors cool. The roofs have overhanging eaves, i.e the roof extends down beyond the walls. This shields the wall from direct sunlight and rain. Openings with jalis let in light but diffuse the hot air. Terracotta tiles, laterite, brick, lime and thatch were common materials — all of which made buildings ‘breathe’.

Nalukettu heritage architecture of Kerala

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images/istock

Interior courtyards were common — the ‘nalukettu’ house is a popular Kerala house form, (naalu meaning four, and kettu —hall), with halls are arranged around a central courtyard. Since hot air travels upwards, the open-to-sky courtyard ensured that air that enters the house travels upwards and exits, allowing a fresh continuous circulation of air.

A house in Kerala built with sustainable materials.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images/istock

Mangalore tiled roof

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images/istock

Baker writes, “A pitched roof made of Mangalore tiles, is as much part of the landscape of the region as a palm tree, and was used from the humblest house to the palace of the former Maharaja of Travancore.” Indeed, the palaces in Kerala were no exception to climate responsive principles. The Padmanabhapuram Palace is one of the most famous for its architectural beauty and simplicity, built with wooden roofs and laterite walls. The Krishnapuram Palace, a 18th Century palace in the Alappuzha district, is another version of the traditional house form — a ‘pathinarukettu’, which uses four courtyards leaving its interiors cool and pleasant.

A view of the Krishnapuram Palace at Kayamkulam near Alappuzha. The palace was built about 300 years ago in the ‘Pathinarukettu’ style.

| Photo Credit:

Johney Thomas

Although family structures and lifestyles have changed, some contemporary architects in Kerala and Tamil Nadu have continued to draw from these principles in their designs. In the past decades, architects like Eugene Pandala, G. Shankar and Benny Kuriakose have been providing an alternative to conventional modern architecture.

Now, a younger crop of architects are also emphasising climate response, indicating that these lessons never get old, and are even more critical now. “In our buildings, we have used burnt clay brick and laterite for the walls, provide large windows with deep sunshades so that the light is indirect. We have designed several houses with no ACs,” shares Amrutha Kishor, founder of Kottayam-based firm Elemental, which focuses on sustainable and climate responsive architecture.

To maintain a comfortable indoor temperature, they use techniques like wind towers, extra insulation for the roof, and windows that skip the glass and use grills with mosquito meshes. “It’s not that climate-responsive houses need to look old school. If clients want a flat roof, we have done it. But we have made it multi-layered with air gaps for insulation. We also focus on orientation, based on the sun and the wind, as using sustainable materials isn’t enough,” she adds.

Red oxide floor

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Tamil Nadu’s coastal climates also share similarities with Kerala, with traditional houses having verandahs, courtyards and tiled roofs. But continued urbanisation, particularly in cities like Chennai, have made these buildings far and few. You can spot in many of the city’s older houses brick and lime plaster, tiled roofs and red oxide flooring. A unique feature of many older buildings in Chennai is also the Madras Terrace Roof.

This roofing system developed as a combination of traditional native techniques and British engineering. In this method, a flat roof is formed by placing thin, burnt bricks on closely spaced timber beams. Unlike sloped roofs, this could be used for multi-storeyed buildings and on a larger scale. With no concrete and a low carbon footprint, it kept indoors cooler.

Madras Terrace Roof of a house under construction.

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Due to practical issues like time and labour, large apartments and majority of independent houses go the mainstream way using concrete as the main material. But some young practitioners like Studio for Earthen Architecture, run by Krithika Venkatesh in Chennai, continue to build houses using lime mortar, earth-based walls and Madras Terrace Roofs.

Keeping an eye out for older buildings is more than just decorative patterns and nostalgia for the past, some of them may hold the key to a cooler future.

(This is the third of a series on finding inspiration in climate responsive architecture around the world.)

The writer is an architect and freelance editor.

Published – September 20, 2024 04:29 pm IST

[ad_2]

Source link