[ad_1]

Every year, during Durga Puja, nearly three crore people visit Kolkata’s pandals — up for just five days. But now, the evolving nature of public art during this season is catching the attention of the art cognoscenti, rivalling any of the big art shows around the world.

Over the last decade, more and more contemporary artists have been involved in conceptualising, designing, and orchestrating massive installations that have gone far beyond conventional pujo pandals. An explosion of creativity post-COVID has only boosted this vernacular vocabulary.

As a novice pandal-hopper, I was recently part of a small preview group, which included art aficionados Lekha Poddar (of Devi Art Foundation), Saloni Doshi (founder, Space 118), artists Sakshi Gupta and Suhasini Kejriwal, and a few diplomats — invited by my artist friend Sayntan Maitra. Over three evenings, we visited intricately-crafted pavilions, met the artists, artisans and technicians behind the installations, and even caught a show by itinerant puppeteers in the intimacy of a private courtyard.

Puppeteers perform a Durga ma tale

A 300-year-old tradition, pandals were originally smaller community-driven initiatives, funded by chanda or donations from residents of a locality to welcome goddess Durga during Navaratri. But with the festivities being both a religious and a cultural event, they became platforms for artists to experiment — from subversive themes to ideas of activism, history and craft. Today, with AI and new media technology, these statements have gotten that much bigger.

Kolkata alone has 4,000 pandals, and some of these surpass what I’ve seen in the global meccas of art such as the Venice Biennale. Poddar echoed the sentiment: “It is better than Documenta [in Germany] or the biennales. It is the epitome of creativity.” The artists use sound, light, art and performance to guide the public around the installations. Picking themes that are current and topical also give people fresh ideas to ponder. Here are a few that caught our eye:

Razor blades and the Constitution

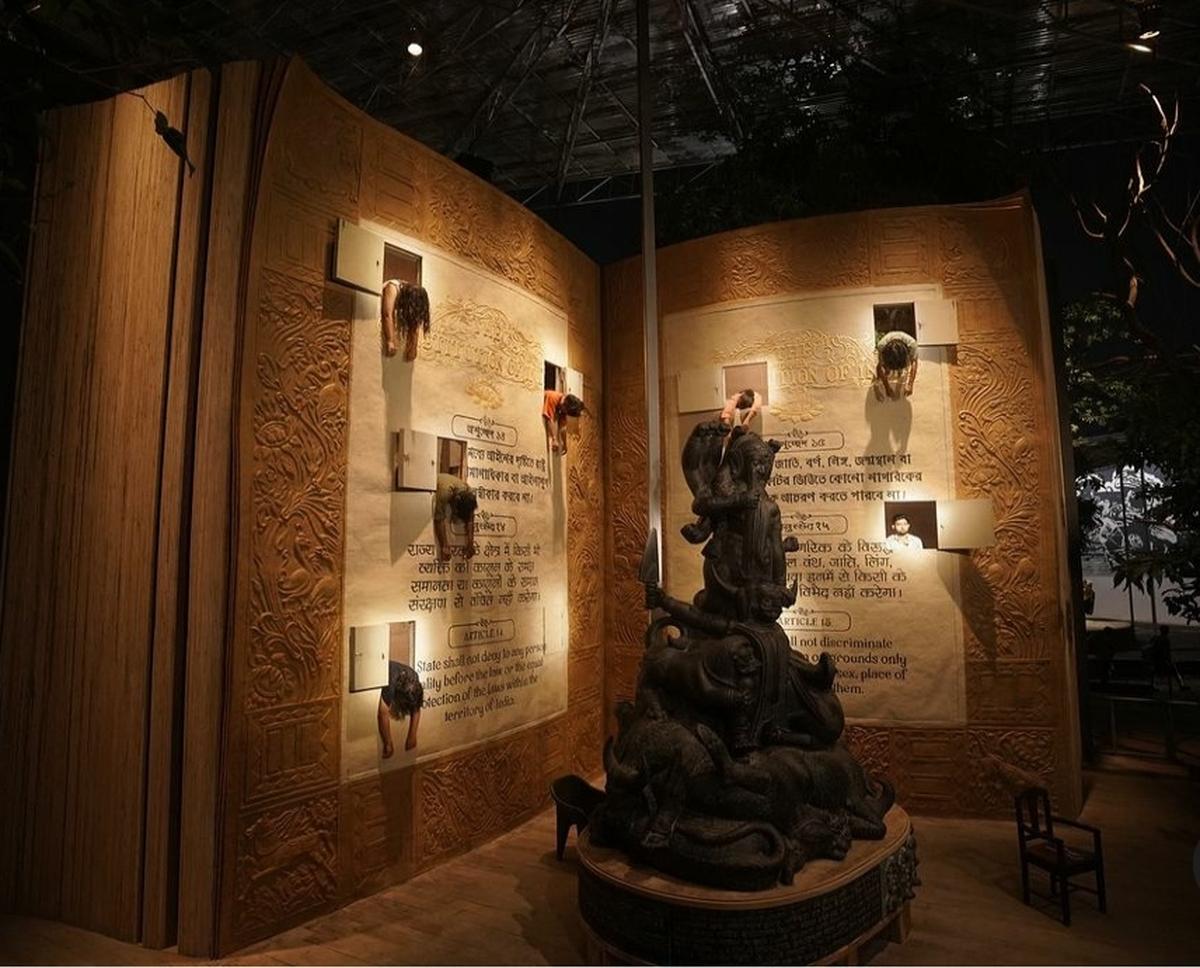

While pandals invoke religious fervour, their art is secular and unique. One of the most powerful ones of 2024 was by artist Bhabatosh Sutar on the threat to the Constitution of India. Spread over 15,000 sq. ft. on two sides of the street, black-and-white portraits with razor blades in their mouths — set against slogans about the rights of the people — led visitors to a 30-foot sculpture of an open book of the Constitution.

Bhabatosh Sutar’s Book of Constitution

Cut-outs in the wood and papier-mâché structure made room for people to stand and recite poems of anguish and introspection in the presence of a multi-armed Durga.

Pavilions are crowd-funded. It is like seeing the monumental edifices once built by royal patrons now moving to the public realm in terms of patronage, support, participation, and acceptance. It is a form of common ownership — a true democratisation of art. Nowhere in the world can you see contemporary public art installations of this scale.

Indigo tales

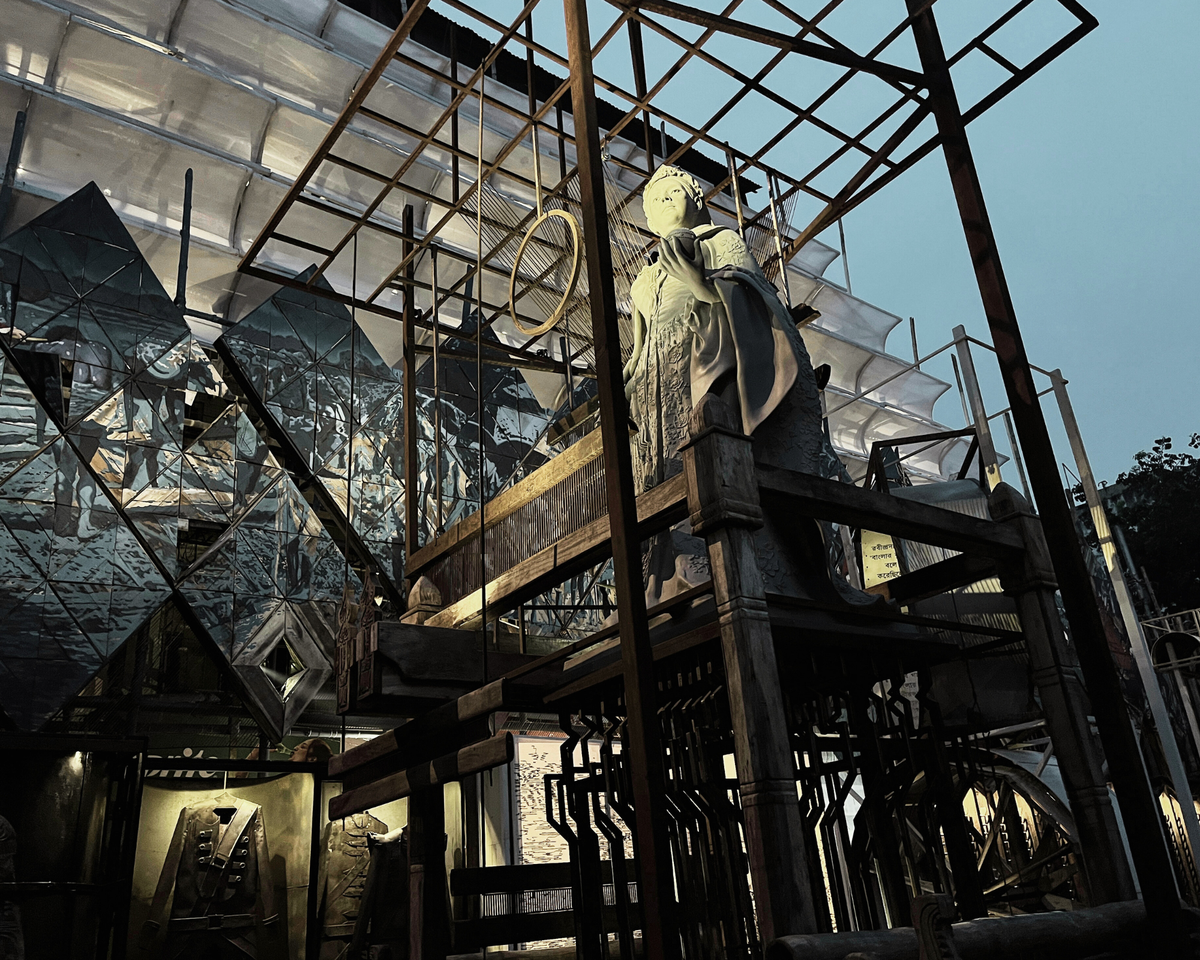

Artist Pradeep Das designed two remarkably effective pavilions. The first, titled Sada aur Neel, tackled the subject of muslin and indigo, and their role in Indian history and colonisation. Walking through a tunnel lined with artwork — that introduced the materials and historical events (for instance, how farmers were subjected to much cruelty under the British) — we entered a large arena full of platforms and a marble statue of Queen Victoria. Along the edge were sculptural references of British army costumes, a guillotine-like structure, and a wall created with wooden shuttles. A lone weaver sat weaving against a backdrop of embroideries depicting ships sailing the seas.

Marble statue of Queen Victoria in Sada aur Neel

| Photo Credit:

Palash Das

The second, spread over 1,850 sq.ft., was a mosaic of the people of the Sundarbans. Titled Aranyak – The Unfolding Narrative, it had plenty of drama: with large mangrove roots, ceramic plates depicting abstract ideas of the delta; and a large map placed on a platform with drawers filled with sketches of the flora and fauna of the region. Both were charged with emotional ethos and provocative suggestions.

Das‘ Aranyak – The Unfolding Narrative

| Photo Credit:

Palash Das

“Durga Puja is an intangible cultural heritage, accredited as the world’s biggest public art festival by UNESCO. Kolkata gets transformed into a giant gallery.”Sayantan MaitraArchitect and curator

Fractured beauty

Maths, drama, sound and light came together in Susanta Shibani Paul’s large-scale contemporary pavilions. In Void (35,000 sq.ft.), the sculptor and costume designer used soulful Gregorian chants in Bengali in a Gothic-style metal interior. A candle flame flickered in multiple projections devised to multiply it four fold. The empty space echoing with the chant, I felt, reflected the void of sensitivity (as a nation) of our time.

The second installation, Resonance (9,800 sq.ft.), was much like a sculpture — of an energy field that led visitors to the main deity. It too shared the idea of carefully calculated surfaces broken with panels of wire and string to reflect light, giving an illusion of mystery. He worked with 350 artists for over two months to put it together.

Susanta Shibani Paul’s Resonance

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

With jamdani at its heart

As I walked from pandal to pandal, I came across themes of climate change, the city’s environment, nature, women’s issues, and more. A distinctive pavilion was Uddan, which showcased jamdani. By Aditi Chakravarty, it addressed the textile craft that is shared between Bangladesh and India.

During Partition, Bangladesh was in turmoil and many weavers crossed the border and created clusters in West Bengal. The pavilion was poetic; its design and execution took over nine months.

The writer is the founder of Apparao Galleries. She was invited to a curated preview by massArt, in collaboration with UNESCO.

Published – October 11, 2024 12:21 pm IST

[ad_2]

Source link