[ad_1]

In 2017, Jose Dominic was invited to dinner with the Salem family in Kochi’s Jew Town. Kenny Salem, an “old friend”, had migrated to Canada and was back to visit his ancestral home. Dominic was expecting his hosts’ famous dishes that evening, perhaps Jewish-style chuttulli fish fry and egg pastels. But there was more in store.

“My friend, the grandson of A.B. Salem, a Gandhian who’d fought in the Independence struggle, wanted to sell the house,” recalls the co-founder of CGH Earth, a renowned hotel and resort chain in Kerala. “With his sister, he made a list of five people, and I was the first person he called. He said he was hoping that whoever bought it would somehow try to keep the place in its original character.” A year later, it was mostly restored and members of the Salem family and the wider Jewish community, who had arrived for the 450th year anniversary of the Paradesi Synagogue, stayed there.

Jose Dominic at A.B. Salem House in Jew Town, Mattancherry

| Photo Credit:

H. Vibhu

The 350-year-old house is the first of a cluster of Jewish heritage bungalows to be restored in the neighbourhood. Others include Mandalay Hall, now a Postcard hotel, and Ezekiel House, also a project initiated by Dominic — all in a bid to revive Synagogue Lane in Kochi’s Jew Town. “The first wave of Jewish refugees, known as the Malabari Jews, came to this coast before Rome was built,” he says. “The second wave, the Sephardic Jews, migrated here in the 15th-16th centuries to escape persecution in Spain.”

Synagogue Lane used to be a residential district up until the 1950s, when the Koders, Cohens, Salems, Robys and many others lived there with large families and staff. The lane, as Dominic told The Hindu last year, was the front yard for these homes “as parties, weddings, rituals flowed out onto the street. Tables laden with food and chairs were brought out in the evenings and the community gathered together”.

A.B. Salem House, before and after

The courtyard in A.B. Salem House

| Photo Credit:

H. Vibhu

Since then, younger generations have left — all except two. Over the decades, the street was taken over by handicraft traders and Kashmiri souvenir shops, and would be dead by nightfall. But now, as Kochi’s smart city project is underway, the street isn’t only getting a facelift, a small group of stakeholders is seeing to it that they also re-engineer some of that “old-world charm” and transform the area into a “living museum”.

“The Paradesi Synagogue is now something like the Taj Mahal of Kerala,” says Dominic. “While there’s been a decline in foreign tourist footfall post-COVID, domestic tourism has exploded.” He cites Vietnam’s Hoi An as an inspiration: a heritage town that was a “contemporary of Mattanchery”, which has been beautifully preserved. “We want to preserve the intangible heritage of the Jewish community, which was very important to Kochi.”

At Mumbai’s Kala Ghoda

Of India’s abundant heritage architecture, buildings of Jewish origin hold a special place. In the last few decades, these private bungalows and estates, as well as public places such as synagogues and hospitals, have become the subject of major restoration work — even as the number of Jews in India dwindled to below 5,000 according to the 2011 census.

“Jewish heritage in India is one of those aspects that shines globally because this is one of a few countries where Jews have not been persecuted historically, even during the World War years,” says conservation architect Abha Narain Lambah. “And India is the only country where the restoration of Jewish heritage has been funded by people of other faiths, not necessarily only by Jewish organisations. That is truly unique.”

Abha Narain Lambah, conservation architect

| Photo Credit:

Umesh Patil

The story of Kochi’s Jewish heritage architecture is mirrored in Mumbai, Kolkata and Pune — the main cities where Baghdadi Jews settled during the 18th and 19th centuries. In Mumbai’s Kala Ghoda district, Lambah and team brought back to life the 150-year-old Knesset Eliyahoo synagogue in 2019, and the David Sassoon Library and Reading Room last year.

The restored Knesset Eliyahoo synagogue

Craftsmen working on the synagogue’s stained glass windows

Knesset Eliyahoo, before and after

Both received financial support from the JSW Foundation, along with ICICI Bank, Hermès and others for the library. “The restoration of the synagogue and library has set the stage for cultural activity,” says Lambah. “An all-faith, peace-music performance took place at the synagogue some years ago, and the library is now a venue for miscellaneous Kala Ghoda Festival events. That gives back to the city in terms of being a cultural melting pot.”

David Sassoon Library and Reading Room

| Photo Credit:

Kartik Rathod

Restored original lighting of David Sassoon Library

| Photo Credit:

Kartik Rathod

Lambah’s next project is to restore the Masina Hospital in Byculla. “It’s the family home of [businessman and philanthropist] David Sassoon, an elegant classical-revival building that is true to its time,” she says. “Our main challenge right now is to raise funds for this.”

Once the funds come in, she intends to begin with the roof. “The building is stunning, there’s a lot of old wood, but also a lot of leakage, seepage and structural issues, especially with the roof and the second floor. You build a building from the ground up, but you sometimes need to restore it from the top down.”

“There are some beautiful temples in Kashmir, such as Ganpatyar in Srinagar, and mosques across Uttar Pradesh that are worthy of conservation,” says Lambah. “The fact is [beyond Jewish buildings], we have less than 4,000 buildings under national protection, and we have no incentives for privately-owned or trust-owned heritage. We are talking about hundreds of thousands of buildings in dire need of conservation with no access to funding.”Abha Narain LambahConservation architect

The Sassoon hospitals of Pune

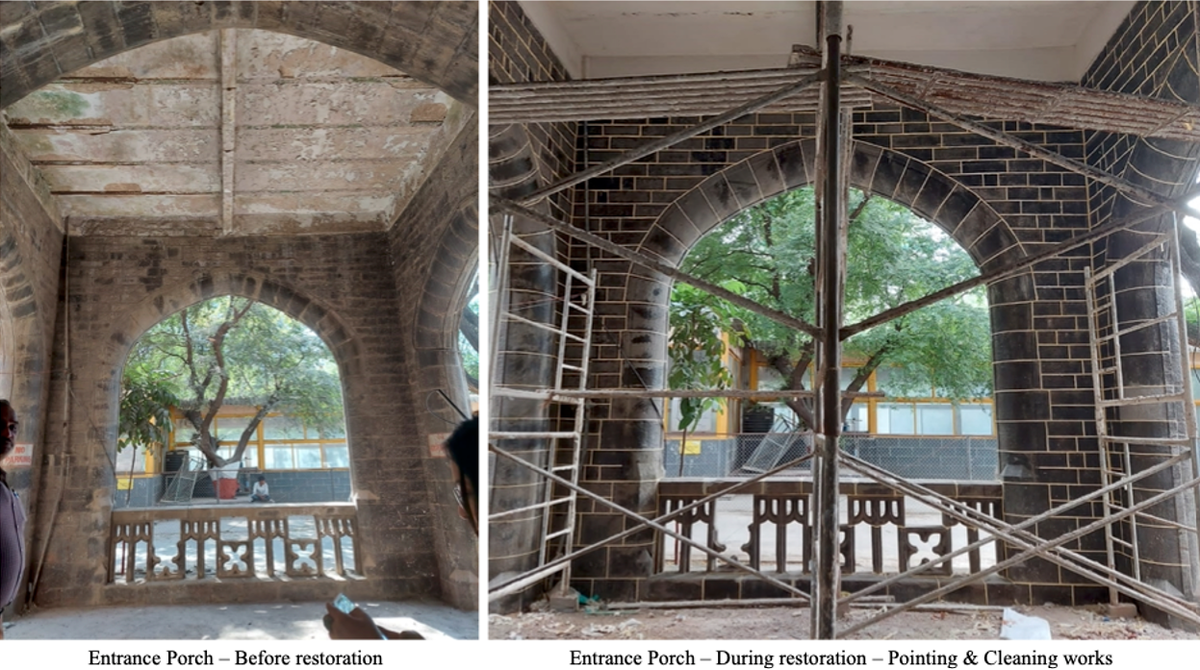

In Pune, on the initiative of the Public Works Department, architect Archana Deshmukh is working to restore two of Sassoon General Hospital’s four historic buildings: the David Sassoon hospital, built in 1867 in the early Gothic style, and the Jacob Sassoon hospital, built in 1906 in the English Victorian Gothic style.

Restoration work at Jacob Sassoon hospital

“One looks more like a fort, the other has high walls and tall, arched windows,” she says. “It’s very rare to see two distinct styles of architecture on one campus.” Her work began in 2023, on a budget of ₹9 crore and ₹6 crore, respectively. The work includes structural refurbishment such as water tightening and mould removal, as well as cosmetic changes, including removing false ceilings, restoring original Lancet windows and murals by a famous 19th century British artist Margaret E. Thompson, who painted the paediatric ward’s walls with illustrations based on children’s rhymes.

Before and after of one of David Sassoon hospital’s rooms

“I always feel that heritage buildings must look like they’ve matured, not acquire a spanking new modern look after restoration,” says Deshmukh. Their usage, too, can evolve. “Both buildings were active as hospitals with 100 beds and 440 beds each, but they can’t keep up with current technology. We decided to put the buildings into adaptive re-use, and are planning to turn them into libraries for PG and UG medical students.” A room in which Mahatma Gandhi had an appendectomy in 1920 will become a museum.

Architect Archana Deshmukh

Synagogues in Kolkata

In Kolkata, two of its three major synagogues, the Maghen David and the Beth El, were restored in 2017 with the help of Jewish trust funds. Skirmishes and allegations around misuse of funds and theft ensued; while others have also pointed out that no proper conservation architects were attached, and the consequences are beginning to show in leakages. Even as the police have brought charges of economic offences (being battled out in court), these synagogues are increasingly important stops on sightseeing maps and walking tours.

“More recently, a group of people led by [social activist] Mudar Patherya has been illuminating a lot of heritage buildings around Kolkata,” says city-based author and researcher Jael Silliman. “He’s done the re-lighting at Maghen David, which looks wonderful at night, with the clock and the steeple. Our clock was made in 1850 and is not working but there is talk of fixing that, too.”

Maghen David synagogue

The steeple and clock lit up

“Former police commissioner Soumen Mitra, who loves heritage buildings, is responsible for restoring the Manasseh Meyer building,” continues Silliman, who has put together an installation of Jewish history in India at the Neveh Shalome synagogue. “We have a gorgeous cemetery in Narkel Danga whose upkeep is being done as we speak. It might actually be the most active place in our community because everybody is old and dying,” she adds drily.

Narkel Danga cemetery

Not all restoration jobs hit the spot, though. “The old Jewish girls school behind Park Street has been converted into a commercial building,” says Iftekhar Ahsan of Calcutta Walks. “They have thrown everything away, slapped plaster and concrete on top of everything. They didn’t even save the plaques. It needn’t have gone that way.” She also mentions the Fabindia flagship in Loudon Mansion — owned by Sir David Ezra in the 19th century, and later in the possession of Keshav Basu, speaker of the Legislative Assembly in the 1940s. “They just kept a bit of the facade, and the gorgeous old building went down. These buildings could have easily been kept as a memory of what used to be, and with adaptive reuse, used in a modern way.” Changes in ownership clearly have their own impact.

“People are beginning to understand the value of heritage. Increasingly, they understand that it is good for tourism. As we’ve become less multicultural, there’s a nostalgia for the past which had communities of various ethnicities, who lived and worked together to build the city [Kolkata] into the beautiful city that it is.”Jael SillimanAuthor and researcher

Back in Kochi

Before she began the restoration work on Salem House, Mridula Jose knew adaptive re-use was their goal. “Looking at older photographs, I tried to understand what some of these houses could have been like,” says the marketing director of CGH Earth, who is leading the work at Salem and Ezekiel House. “Different generations living in the same house kept adding elements, so when we began, we could see layers of time. We decided our restoration work would approach it as an amalgam of different eras of the family.”

It’s why they retained elements like the original facade, the main door, the terrazzo and terracotta floors, old wooden beams and doors, but cleaned up the flow of the place, so they could carve out four bedrooms and a courtyard. A space that was also reminiscent of a certain lifestyle, where neighbours walked through houses freely and much of the day was spent communing on streets.

AB Salem House

Ezekiel House, once called Nila Manzil, has changed many hands over the years; and been used variously as a soap factory, godown and shops. “We had to consider how to bring back its residential use,” says Jose, “so our first step was to clear out all the additional temporary constructions so we could create the hall, rooms and courtyard and room for a cafe as well.” Both boutique hotels are slated to open for business this October.

Tony Joseph, chief architect at Stapati, had something similar in mind for Mandalay Hall. “I’d bought the 350-year-old building some time back,” he says, “after I found that most buildings on Jew Street had been destroyed or mutilated, taken over by people with a different imagination of what tradition and heritage is.” Mandalay Hall was built by the eponymous trader who operated in Burma.

Architect Tony Joseph

Before and after of a portion of Mandalay Hall’s exterior

After some issues with clearances from the Archaeological Department, Stapati’s restoration work preserved the plaque, some of the original paintings, the lime plaster, and replicated their distressed look in the other rooms. It is now a five-room property, initially an “art hotel”, now under the aegis of Postcard.

Syncretic advantage

Beyond boosting tourism, creating cultural centres, or simply the altruistic purpose of heritage conservation, everyone we spoke with felt that India’s Jewish-origin architecture appears to advocate a syncretic, community-led way of life — which adaptive re-use could help continue in the 21st century. Deshmukh highlights the importance that “giving back” holds in Judaism. Lambah points out that the Sassoons’ philanthropy was integral to the creation of Bombay as we know it today.

Dominic narrates the story of Sarah Jacob Cohen, an embroiderer in Jew Town who died at the age of 97, and her Muslim helper Thaha Ibrahim, who eventually set up the Sarah Museum in her memory. And Silliman underlines the “sacred geography” of Kolkata — the Armenian and Chinese churches, the Guru Nanak gurudwaras, the Kalighat temples — mapping a city that became a wellspring of many faiths, including the “Hare Krishnas”, the Sikhs and the Jews, from the 19th century onwards.

Jael Silliman

“More than religion, I feel conservation is for communities,” concludes Lambah. “I consider myself a part of the community that lives with the David Sassoon library; it doesn’t matter if I’m Jewish or not. It is our collective responsibility that these landmarks of a past generation are transferred to the next.”

The writer is an independent journalist based in Mumbai, writing on culture, lifestyle and technology.

[ad_2]

Source link