[ad_1]

As the world’s largest elections are underway, all eyes are on digital platforms and the role they are playing in influencing the electorate. However, it may also be time to question the effectiveness of the Model Code of Conduct (MCC) set down by the Election Commission (EC) in ensuring free and fair elections in India.

Section 126 of the Representation of People Act, 1951 prohibits the display of election matter to the public through television or similar apparatus during the 48-hour silence period ending with the hour fixed for the conclusion of polls. The EC in its various notifications has clarified that ‘similar apparatus’ under Section 126 includes social media as well. Despite clear rules prohibiting political campaigning during the silence period, a study conducted by the CSDS-Lokniti has found political parties to be spending substantial money on advertising campaigns on social media during this time.

Social media campaigns

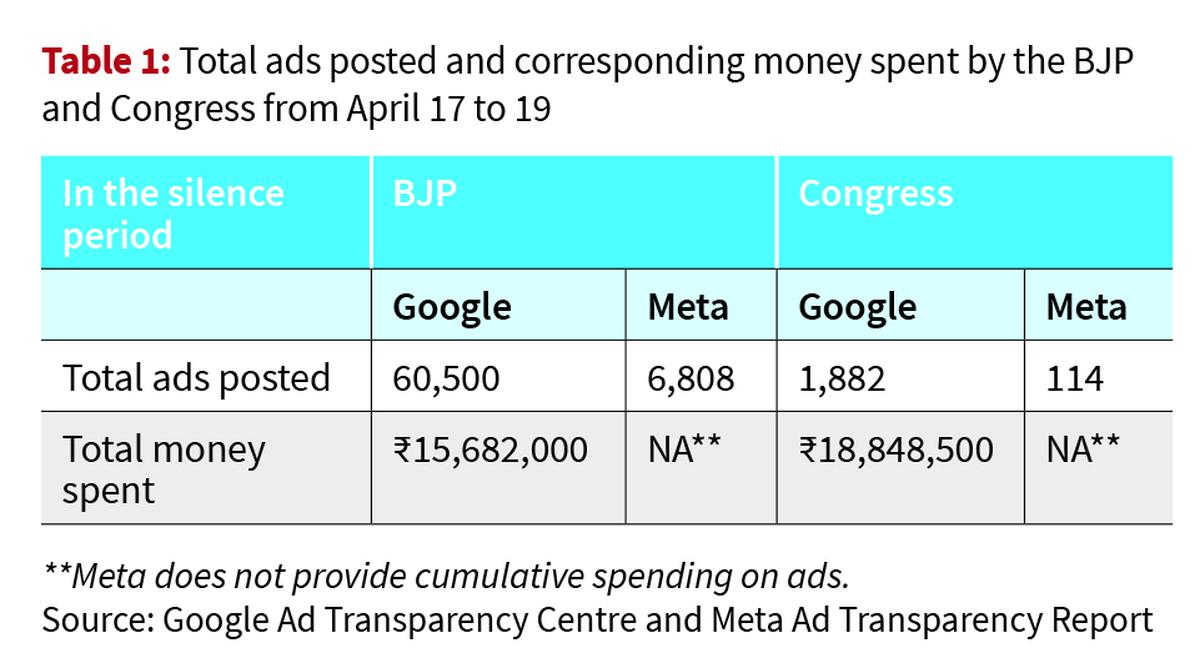

It was found that BJP posted 60,500 ads from April 17 to 19, 2024 on Google and 6,808 on Meta platforms, while the Congress posted 1,882 and 114 ads respectively during the same period (Table 1). This revelation is note-worthy since the Internet penetration in India is over 50%.

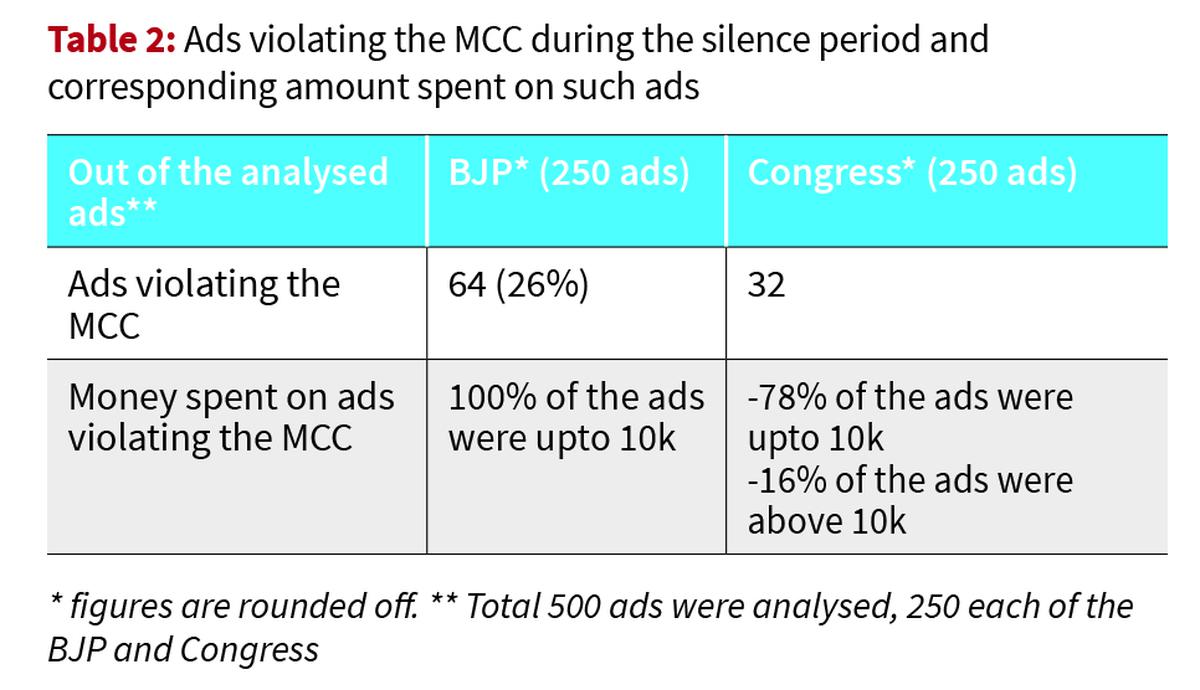

Out of the total ads posted from April 17 to 19 on Google, 500 ads, 250 ads posted by the BJP and another 250 posted by the Congress, were selected for analysis using randomised selection. Out of this sample, 64 ads posted by the BJP and 32 posted by the Congress were found to be targeted to States/constituencies that voted in the first phase of elections (Table 2).

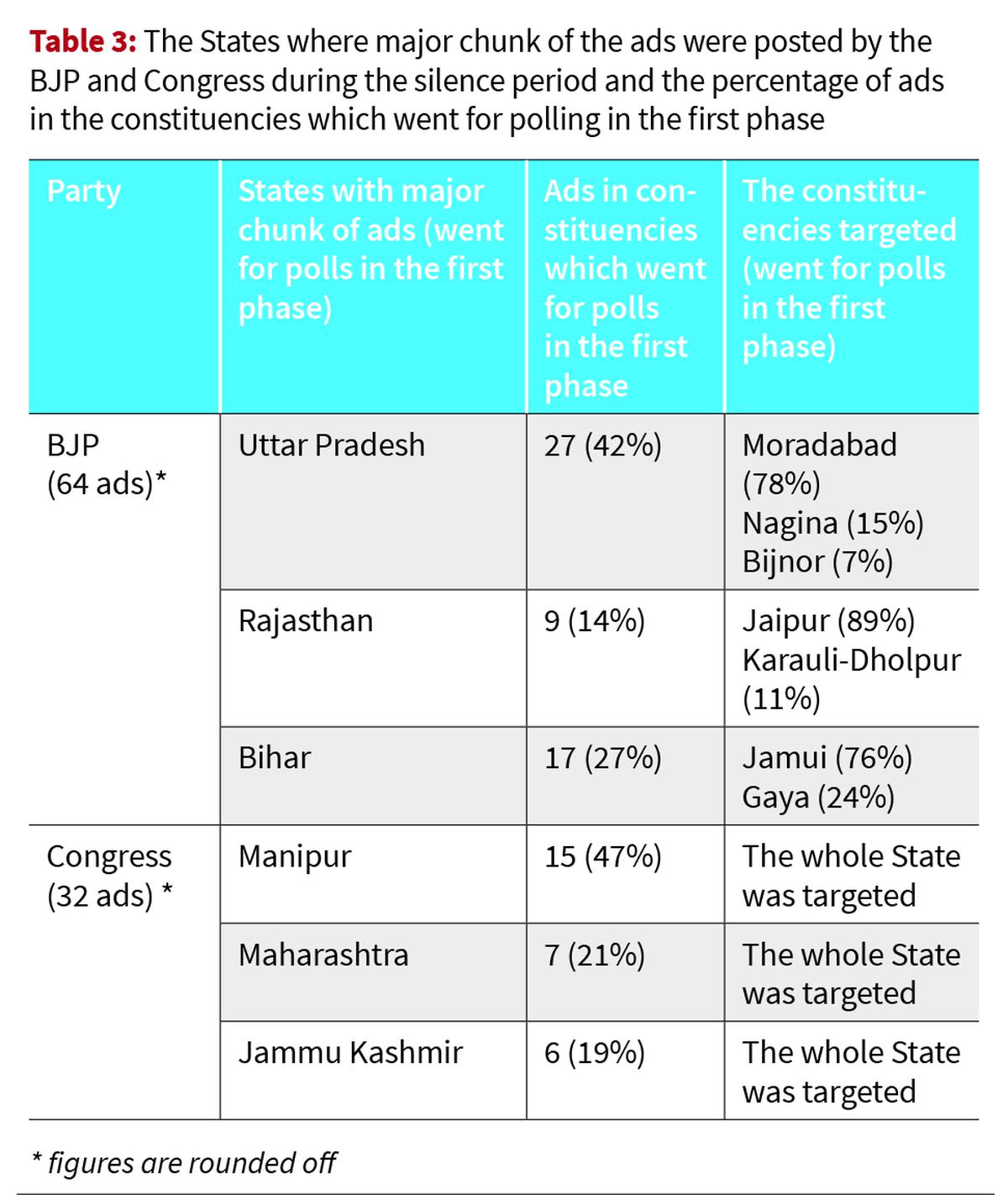

This study revealed that 13 out of every 50 ads of the BJP were aired during the silence period in constituencies participating in the first phase of elections. Notably, political ads were observed in 11 States and Union Territories preceding the first phase of elections, with several States being majorly targeted (Table 3).

This data underscores the strategic placement and targeting of political advertisements during critical phases of the electoral process. Of the total number of Congress ads, States voting in the first phase of elections were targeted as a whole. However, except for Haldwani in the Nainital constituency in Uttarakhand, no other Congress ads specifically micro-targeted any poll-bound constituencies during the silence period (Table 3).

The strategy of geotargeting

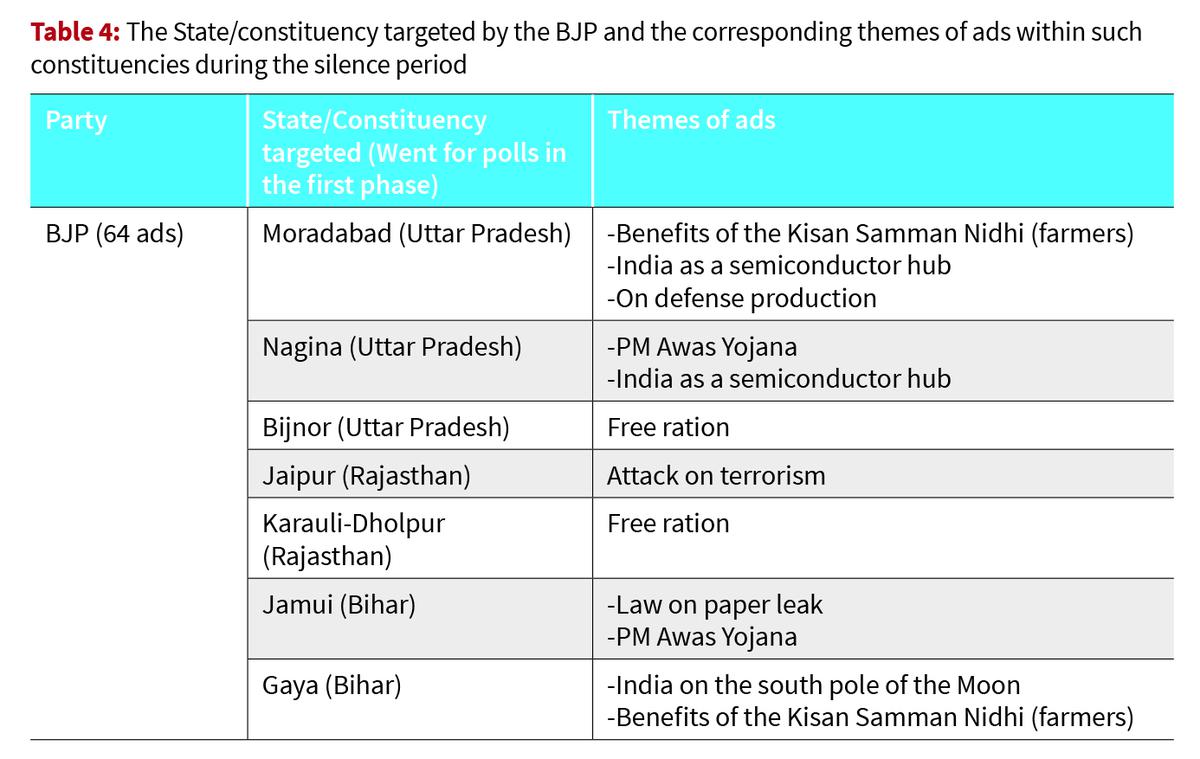

During the silence period, the BJP’s digital campaign showcased an impressive level of location based targeting precision, evident in its focus on specific locales such as a panchayat in Baghpat, Uttar Pradesh, and Belthangadi in Karnataka. These instances provide just a glimpse into the party’s widespread use of tailored strategies. Additionally, the BJP targeted the Nagina constituency in Uttar Pradesh with a substantial number of advertisements during this crucial period, recognising the historical significance of the Muslim-Scheduled Caste (SC) combination in securing victories in this constituency (Table 4). However, the northeastern region remained largely overlooked throughout the silence period.

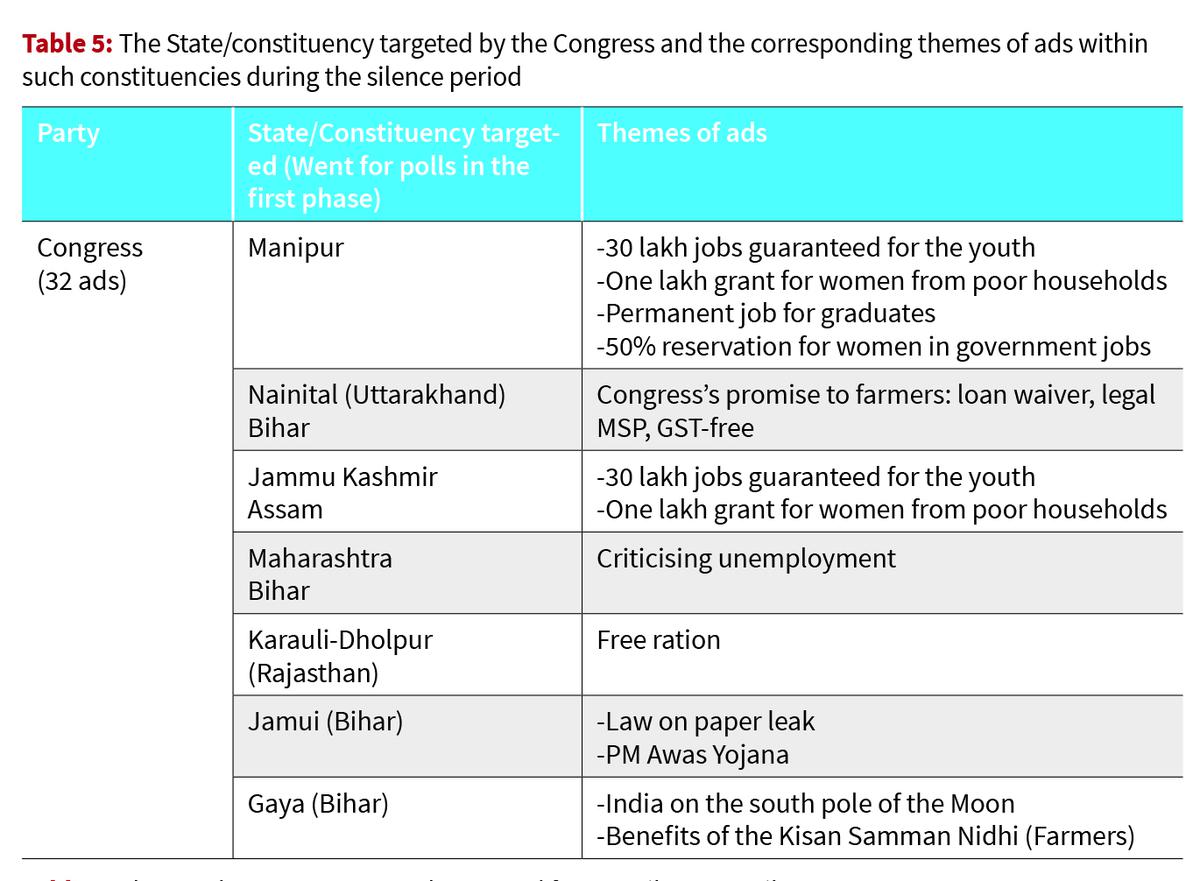

The Congress avoided constituency-level targeting. In fact, 42% of Congress ads specifically excluded the poll bound constituencies from the targeted States which went for polls in the first phase. All the constituencies in Rajasthan, Assam, Bihar and Chhattisgarh which voted on April 19 were excluded in the ads posted by the Congress in these States. Similarly, in ads targeted to Madhya Pradesh, all poll-bound constituencies, except Sidhi, were excluded. Unlike the BJP, the Congress was found to be vigilant in its presence across Manipur with a major chunk of its targeted ads focusing on all the major themes during the period of analysis (Table 3 and 5).

The Meta campaign

In the case of Meta, the parent organisation of both Instagram and Facebook, both the BJP and Congress are seen to have run ad campaigns during the first phase of the election. This analysis is based on their official social media handles.

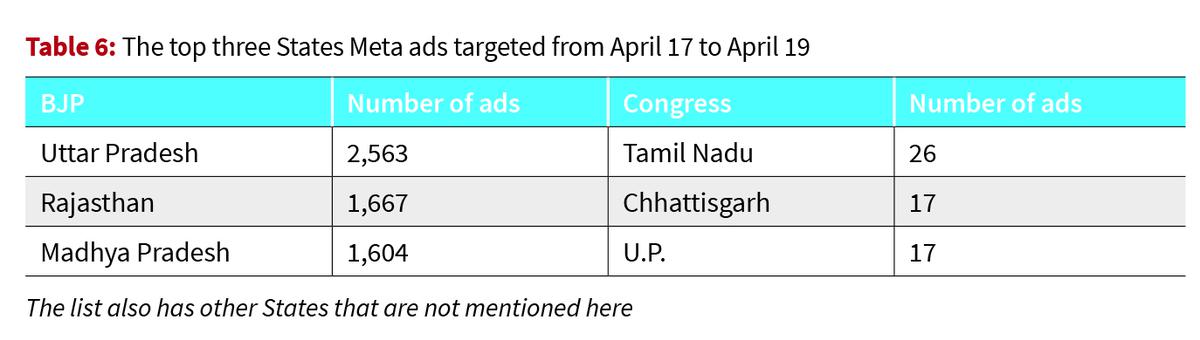

Unlike Google ads, none of the ads on Meta platforms were pin code-specific. Still, they were State-specific, stating that ad campaigns operating in a particular State apply to the territorial area of the whole State, including those constituencies involved in the first phase of elections. Of the 6,808 ads posted by the BJP, several ads were circulated in more than one State. For Congress, which posted 114 ads during this time, Tamil Nadu, Chhattisgarh, and U.P. were the main targets (Table 6).

This data throws light on the ad campaigns by the two major parties on Meta from April 17 to 19, the official silence period for the first phase of the election.

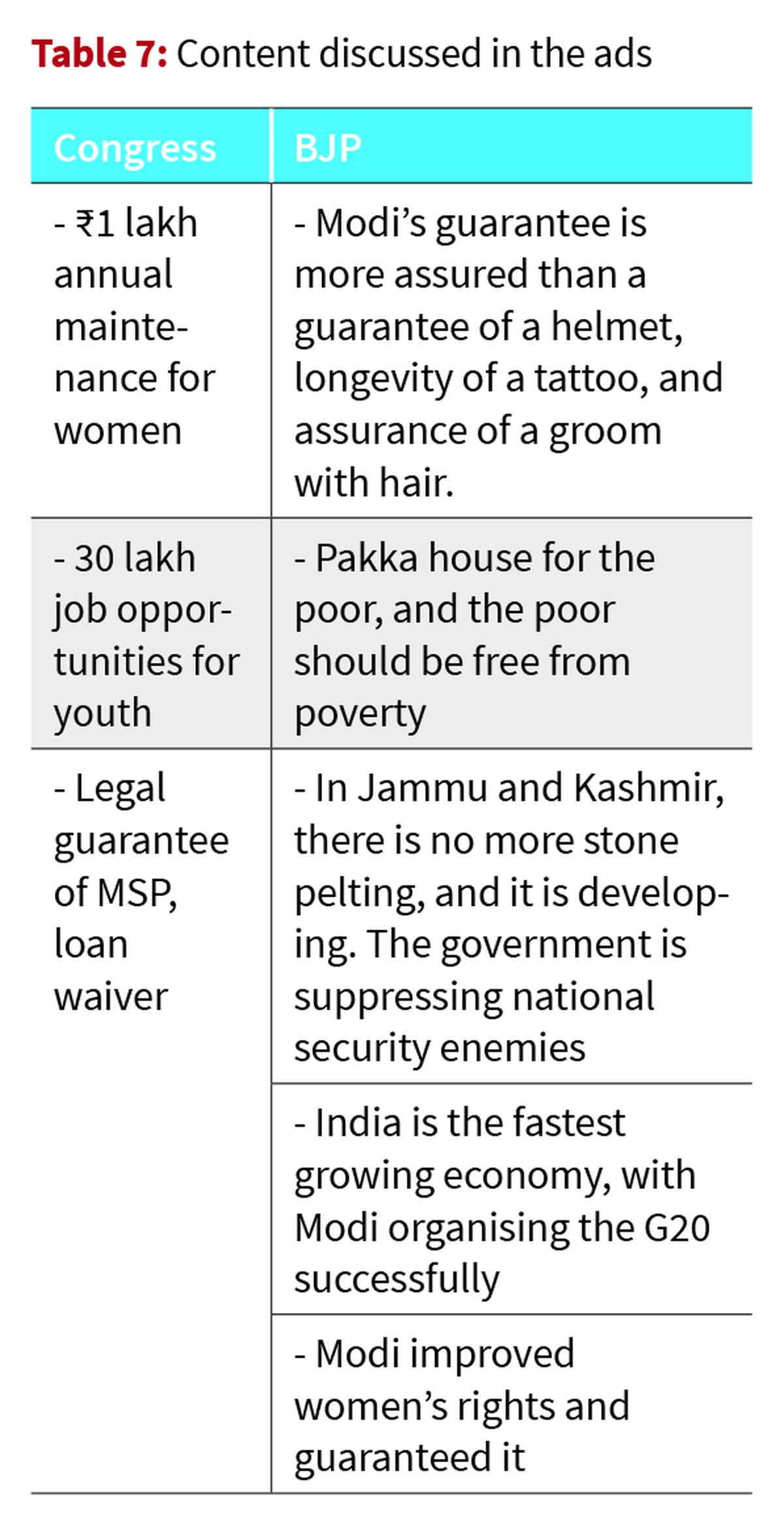

There is a clear lead by the BJP in the sheer number of ads posted. There is also a more diversified campaign from the BJP, in contrast to the Congress, as can be evident from the language in which the ads are posted. The BJP has posted ads in more than seven languages, while the Congress has posted only in three.

In the lead-up to the first phase of elections, it became apparent that political parties are stretching the boundaries of the MCC, particularly through digital media ad campaigns. There seems to be a lack of preventive as well as punitive actions taken to address such violations, raising questions about the effectiveness of the MCC in ensuring free and fair elections.

By utilising location-based targeting in digital campaigns and focusing on key locales, it seems that parties may have found ways to reach voters during a period when campaigning is restricted.

As the second phase of Lok Sabha elections approaches, it may be worth considering these observations regarding adherence to the MCC.

Sanjay Kumar is a Professor at CSDS, Aditi Singh is an Assistant Professor at O.P. Jindal Global University, and Abhishek Sharma, Hana Vahab, Subhayan Acharya Majumdar are researchers with Lokniti-CSDS.

.

[ad_2]